FINE The wine magazine

REIMITZ or the Beauty of Wine

(Text Till Ehrlich, photos Marc Volk)

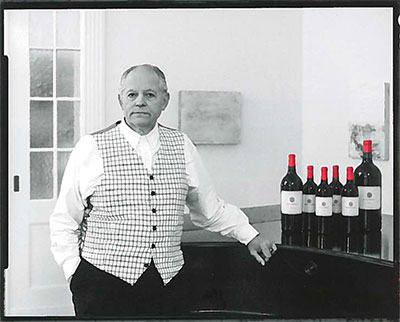

Sangiovese solo: "REIMITZ" is a new Tuscan cult wine from the Chianti Classico. But it is deeply rooted in the tradition of the finest Italian wines. This is what the winemaker Klaus Johann Reimitz stands for, who produces this rare wine single-handedly.

Klaus Johann Reimitz has helped to create twenty-five vintages of Sergio Manetti's Montevertine winery in Radda in Chianti Classico, including the single-varietal Sangiovese "Le Pergole Torte", a jewel of fine Italian wine, which is at least as important as Tignanello and Sassicaia in terms of its style-defining significance for the Italian wine renaissance. Since 2011, Klaus Reimitz, born in 1951, has been producing a single-varietal Sangiovese on his own. Only one thousand five hundred liters of it were bottled for the premiere. The grapes grow in a small plot that belongs to the Poggio al Sole winery in the Tavarnelle district, a place that lies in the heart of Chianti Classico above the thousand-year-old Vallombrosan abbey of Badia a Passignano, just half an hour from Florence.

The first vintage was already a success. It embodies the taste of the Sangiovese grape in a direct, graceful way: not loud, but very harmonious, fine and differentiated. One grape variety, one vineyard, one barrel, one winemaker, one wine. No oak aroma, no toasty notes, no kitsch. No Cabernet, no Merlot, no Canaiolo, no Colorino.

This red wine, which succinctly bears the name of the winemaker, "REIMITZ", is something like the sum of a Tuscan winemaker's life. The label appears unspectacular, elegant, and testifies to style and timelessness, as if it had been around for decades. But it was only designed for the "REIMITZ" in 2013.

This wine is about seemingly simple things, about good color, good aroma, good taste. Nothing artificial, just that it is not easy to bring the simple to perfection. Just as in fine cuisine, the skillful preparation of egg dishes or pasta is one of the most difficult things. Simple does not mean that it is easy to do. You have to really understand the old Etruscan grape variety Sangiovese. To do this, a winemaker needs experience from the ups and downs of many vintages, from good, average, difficult. In short: an intensive winemaker's life. "Sangiovese is a very delicate, fine thing. Not a farmer's wine," says Klaus Reimitz.

You have to imagine Tuscany at the end of the 1960s as an agricultural landscape that had nothing to do with what it looks like today. For a long time, European history was written here, but at the time it did not seem as if it had a future. The Tuscan landscape, which had included viticulture and rural agriculture since Etruscan times, was in decline. The old was no longer viable and the new was not yet visible. Tourism was out of the question. A paralyzing silence hung over the Tuscan hills: many farms and country estates were deserted, fields, pastures and vineyards lay fallow. And with them, Tuscany's millennia-old rural culture was gradually lost. Sangiovese, the blood of Jupiter, which had been cultivated here since Etruscan times, was often mixed with Chianti and diluted with white wine from the mass-produced Trebbiano variety.

Winegrowing was economically in ruins, as was all traditional farming. As a result of sharecropping and rural exodus, no investment had been made for decades, neither in vineyards and wineries nor in brilliant ideas and concepts on how to revive the once important Tuscan winegrowing. But even in its decline, the Tuscan hills showed their beauty, because beauty contains a hint of the eternal. This beauty attracted a small group of people who had been touched by the charm of Tuscany.

In 1967, steel merchant Sergio Manetti (1921 to 2000) from Poggibonsi acquired one of these abandoned properties: Montevertine - the mountain through which the wind blows. The farm was originally intended to be a holiday home. But the hill with its farm, which had been in operation since the 11th century, and almost forty hectares of land captivated Manetti. He was not just a businessman, but a well-educated person with a sense of culture, literature and the fine arts, who particularly appreciated food and wine. As early as 1968, Sergio Manetti had two hectares of Sangiovese vines planted, and with the 1971 vintage he proudly presented his first wine, a beautiful Chianti Classico, which gave him the courage to continue on this adventure.

At that time, a young German, Klaus Johann Reimitz, came from the Rhineland to Perugia to learn Italian and study art history at the Accademia di Belle Arti Pietro Vannucci, founded in 1573; he wanted to become a restorer. Here he met the professor and art historian Roberto Manetti, the younger brother of Sergio Manetti. Roberto gave the young Reimitz some advice: "If you do something, Klaus, do it properly and seriously."

In May 1981, on his thirtieth birthday, Klaus Reimitz came to Montevertine. The silence that reigned on the hill was one of the first intense impressions of this place: "There were no tourists, not even the twittering of birds, because songbirds were still hunted and eaten in Tuscany at the time," he remembers. At the time, he wanted to become a restorer and only stay at the winery for a year. But things turned out differently; he decided to go into winemaking, and one year turned into many. Klaus Reimitz married Sergio Manetti's daughter. He developed the wines of the Azienda Agricola Montevertine together with his father-in-law. Klaus Reimitz helped to create a total of twenty-five vintages of Montevertine.

"I was young," he says today. "The joy was being involved in the creation of a wine that was beautiful." The concept of beauty is perhaps a key to understanding Klaus Reimitz and his wine. It is not based on a belief in optimization based on technology, but on aesthetically educated thinking. Reimitz does not like to describe wines as great. He calls a wine that he thinks is successful "beautiful," and one suspects that the word embodies the entire history of ideas about beauty, in particular the idea that the ordering form of beauty can lift the heavy into lightness.

The Montevertine winery has renewed the tradition of fine Tuscan wine from within, although or because it is a relatively young winery by Tuscan standards: the 1970s were the phase of Montevertine's development, the 1980s saw the discovery of Tuscany and its wines, and the 1990s saw the worldwide fame of Montevertine, the symbol of which was the top wine "Il Pergole Torte".

Sergio Manetti died in November 2000 at the age of seventy-nine. After his death, Klaus Reimitz managed the generational change, with responsibility being passed on to Sergio's son Martino Manetti. 2005 was Klaus Reimitz's last Montevertine vintage. He still lives on Montevertine today. "Here I am protected, I have my surroundings protected; in Asia, for example, I would be completely alone with my wine."

His wine, the "REIMITZ", comes from a one-hectare vineyard plot that Klaus Reimitz affectionately called "Boronzky" after his Russian great-grandmother. The fact that "REIMITZ" exists is not least thanks to loyal friends who stood by Klaus Reimitz and encouraged and supported him in his plan to make his own wine. One of them is the Swiss Johannes Davaz, the owner of the Poggio al Sole winery. He leased the vineyard plot to him and lets Klaus Reimitz make his own wine in his own barrels in the Poggio al Sole wine cellar.

Like Pinot Noir, Sangiovese is considered a difficult and demanding variety, both in the vineyard and in the cellar. And Sangiovese alone is a particular challenge for a winemaker because the variety ripens slowly and late, which is why it is at risk from wet weather in the autumn. It can have very hard tannins and acids, especially when yields are too high and the grapes have not been able to ripen. Too much heat is also detrimental to its quality, and the wine then becomes one-dimensional, alcoholic and sweet, as is known from some Brunello vintages.

In contrast, the cooler altitudes of Chianti Classico such as Tignanello, Montevertine or Poggio al Sole offer ideal growing conditions for Sangiovese in terms of elegance, complexity and longevity. But here too, quality can only be achieved through a high level of care in the vineyard and with a great deal of sensitivity and experience in the cellar. If these factors are not present, the Sangiovese quickly takes on a rough appearance. That is why the basic idea of the Chianti Classico wine is based on an idea from the Italian statesman and winemaker Barone Bettino Ricasoli (1809 to 1880) in 1840. According to this, the roughness of the Sangiovese should be made more pleasant in a cuvée with varieties such as Canaloio and Mammolo. Up until the 2006 vintage, dilution with white wine varieties such as Malvasia and Trebbiano was even permitted under wine law.

The paradigm shift in Italian top-quality winemaking began in the late 1960s. It marked a break with Ricasoli's outdated Chianti formula from the 19th century: instead of diluting the Sangiovese with other varieties and making it "softer", as the Consorzio del Vino Chianti Classico Gallo Nero prescribed, the aim was now to increase quality through better care in the vineyard and in the cellar. This was achieved by drastically reducing the harvest quantity, by using higher-quality vines and increasing planting density, which also naturally reduces the yield.

Another decisive factor was a different cultivation style, which broke new ground in Italy through the use of barriques and the introduction of targeted biological malolactic fermentation. The first wine of this new era was the 1968 Sassicaia by Marchese Incisa della Rocchetta in Bolgheri in the Maremma, followed in 1971 by the first vintages of Tignanello by Marchese Piero Antinori and Montevertine by Sergio Manetti in Chianti Classico. These wines were very different in style, but the groundbreaking philosophy that had produced them connected them, changed top Italian winemaking for good and led it into the modern age.

With Sassicaia, the key idea was to completely omit the Sangiovese, which has ripening problems in Bolgheri, and to rely on the Bordeaux varieties Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. With Tignanello, on the other hand, the majority of the cuvée consisted of Sangiovese and was composed with around twenty percent Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. If you consider that the climate in Tuscany was cooler in the 1970s and 1980s than it is today, it is clear why ripening problems in Chianti Classico were also harmonised with Cabernet.

The path of using Sangiovese solo, which Sergio Manetti and Klaus Reimitz were the first to take at Montevertine, was considerably riskier. The failure of a vintage always represents an economic risk in viticulture. Choosing a single grape whose weaknesses cannot be compensated for by adding another grape variety in difficult years forces you to study this grape variety even more intensively so that it can produce wines whose taste is based on harmony and finesse.

Since Klaus Reimitz sees the natural fruit and structure of Sangiovese as something fragile and delicate, he does not use barriques for maturing the wine, but rather oval 1500-liter barrels. "The wood is not meant to flavor the wine," he emphasizes, "it is just a container in which my wine matures." Reimitz gives his wine the time it needs in each phase of development. Depending on the vintage, the wine matures in the barrel for twenty-four to twenty-six months. There is no fining, no filtration. During the long, careful maturing process, the wine becomes stable on its own.

Every step in the winemaking process is done with care and consideration. For Klaus Reimitz, the time of the yeast extraction is the decisive moment in the winemaking process because, in his opinion, it has a significant influence on the quality of the wine. "Before the yeast extraction, I try a lot, think about it, try again, think again, and eventually I come to a decision."

In every vintage, Klaus Reimitz is concerned with "how far you can go with the wine." He is not concerned with which vintage is the better, because every vintage is different, has its own character. Like the 2011 vintage, which shows a beautiful transparent ruby red in the glass. Its scent combines intensity with freshness and grace, cool with warm aromas. Its taste unfolds with enormous complexity and polish, an unpretentious nature that is direct but not coarse, but graceful and weightless. The 2012 vintage has enormous substance and great potential; it is a wonderful wine with its own expression, which composes its freshness with silky tannins and wild cherry fruit in such a sublime and lively way that one can sense the intensity of taste it will release when it has reached full maturity for consumption one day.

Klaus Reimitz also takes his own approach to marketing in order to maintain both his independence and his quality standards. Because this is only possible with a very limited production that he can manage completely on his own, there is very little of it, and you can't just buy a bottle of "REIMITZ" in stores. For the 2011 vintage, there were only fifteen hundred liters in total. The winemaker divided it into forty-seven lots. Each lot contains thirty liters, bottled in twenty-four standard bottles (0.75 liters each), six magnums (1.5 liters each) and one double magnum (3 liters). The lots were sold directly to wine lovers. This will also be the case with the following vintage, 2012, whose lots will be available this spring.

Before Klaus Reimitz became a winemaker, he restored Renaissance furniture and restored it to an earlier state of preservation. It is part of the restorer's identity to admit that he has restored something: you can see it with a magnifying glass. The winemaker Reimitz takes a similar approach: he gets the most out of the grape. The wine can never be better than what the grape can produce. Reimitz does not construct wines that go against nature and does not rely on the short-term effects of aromas, color, scents and consistency. Instead, he looks for the values that can come together in the wine over the long term and remain alive throughout its entire development phase. This is not about the effect of individual components such as acidity, tannins or alcohol, but about expressing the character of the wine over its entire lifespan.

Lovers of elegant Chianti wines are always enchanted by the inspiring finesse, freshness and depth that characterize the Sangiovese “REIMITZ”.

He developed the Montevertine wines in this way - and also the "REIMITZ". The inner harmony of the wine is not a reduction in the sense of omission, as is practiced with forced wine concentrates or essences. Rather, the harmony means a revival, a condensation of the essential.

For Klaus Reimitz, the constant balancing and the possibilities of this process are the decisive factors in winemaking: When is the right moment to do something or not? Should you wait a moment before removing the yeast or not? This also includes the knowledge that decisions in winemaking are irreversible and that a wine never forgets anything. "The sum of all these experiences results in quality. There is no such thing as too much, it is like a birth, the wine is always in motion." Klaus Reimitz does not rely on measurements and technical parameters, but on his instinct, his intuition formed through experience. "In the end, you are just your nose and your mouth."

A great wine, like a great work of art, cannot be completely thought out and planned. This characteristic is part of the essence of winemaking: it is expressed stylistically in the wine through the simultaneous combination of finesse and intensity. It can also contain breaks, which makes it inimitable and unique - in other words, beautiful. "REIMITZ" is a plant that expresses the beauty of Tuscan wine.

Issue 1/2015

Leave a comment